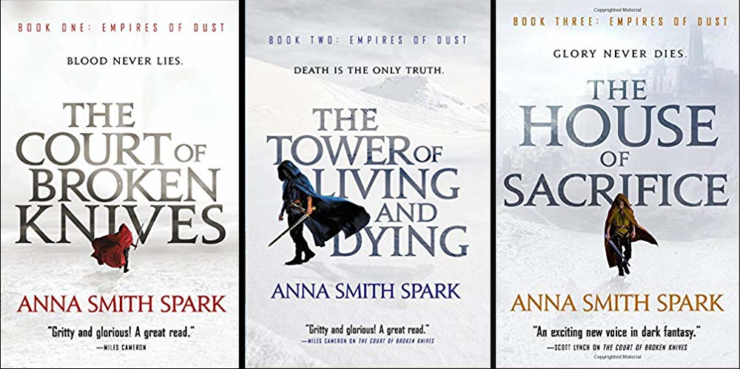

To raise awareness for virtual non-profit The Pixel Project’s mission to end violence against women, r/Fantasy has been hosting a series of AMAs. One of this week’s featured writers is Anna Smith Spark, the author of the Empires of Dust trilogy and the blurb-appointed Queen of Grimdark. While answering fan questions, she ended up doing a very illuminating deep dive on grimdark as a genre, from its historical roots to its inherent “political dimension” to why she considers it less misogynistic than “heroic” and “sunny” epic fantasy. Here are some of the AMA’s highlights.

On grimdark’s very old roots:

As I’ve said and Joe Abercrombie said sitting next to me at an event we did together just last week: the Iliad is a work of grimdark fantasy. The Iliad is the first piece of literature in western Europe.

Seriously, the terrible thrill of violence, the desire for power … this has been a constant of human history. Violence – gendered violence – has been a constant of human history. Fear of the dark, of the monsters out there and the monsters inside one’s own house, inside one’s own self, has been a constant. People have always told stories that are ambiguous in their attitude to power and to violence, that explore the pleasures and horrors of war. People have always told stories of demons and dark powers, and felt a thrill thinking of themselves welding such power. Grimdark fantasy is a modern genre dealing with very old things.

On how grimdark differs from dark fantasy:

To me ‘grimdark’ is distinct from dark fantasy in that it has a very clear political dimension, a narrative cynicism that unpacks ideas like ‘leadership’, ‘power’, ‘good and evil’ and raises some uncomfortable questions about how we thinking about them. Grimdark asks questions about how power operates, uses fantasy to comment on huge issues of human morality and motivation, asks us to think a bit deeper about what we might do. It’s about cynicism, self-criticism, it’s actually very much a genre that criticises and politicises ‘righteous’ violence.

On how the misogyny in grimdark can be political:

Honestly, I think that grimdark has far less of a problem with misogyny than more ‘heroic’ sunny good versus evil epic fantasy. Because grimdark is political. It shows the reality of power, that the ‘hero’ isn’t necessarily a hero, that violence is a terrible thing. The erasure of women from grimdark novels (including my own) is to me a profoundly feminist act – this is male violence, toxic masculinity, and I don’t want women to be a part of that. When I use the terms ‘soldiers’ and ‘men’ interchangeably, I’m calling out gendered violence.

Take R Scott Bakker’s SECOND APOCALYPSE series. These books are to me the greatest achievement of grimdark fantasy by one of the greatest writers of fantasy full stop. They are often criticised as mysogynistic. And that’s the point. The world of Eawa is horrifyingly, terrifyingly misogynistic. The men see women only as dumb sexual objects created to pleasure men. And the world is a horrifying, impossibly bleak, impossibly violent place. There’s no space for love, for happiness, for peace. The erasure of women in Eawa leaves the men damaged, trapped in their own violence, unable to find anything beyond violence. Because it is a place of misogyny, Eawa is a place of sterility and death. The men are trapped in their toxicity. They can only rape and murder. They cannot love. And that’s the point. The shining blue-eyed blond-haired saviour hero … is a toxic terrifying emotionally empty fascist.

It’s in the far more simplistic fantasy of the hero as a hero that the problem lies.

There are some bottom of the barrel ‘grimdark’ novels that are just mindless violence, sexual violence and gore laid out pretty uncritically for male titilation and shock factor, yes, sure. The final few series of Game of Thrones, the stuff with Ramsey Bolton in particular … that was just horribly vile trash. But at its best grimdark is a comment on violence, a reminder of what actually violence, even violence in a ‘good cause’, actually means.

Which, in the end, is more problematic – a story in which a woman does not always consent, is shown enduring violence, or a story in which the unthinking assumption is that a woman is always willing when the hero wants it?

In my own books, Thalia is the traditional love interest, yes. She’s not a kickass woman. I have concerns about the very notion of a ‘kickass’ woman, in that it suggests that the best thing a woman can be is just like a violent man. Thalia is passive, her identity defined by the men around her – as most women’s identity was defined for most of human history. So I wanted to tell her story in those terms. She is the only character who speaks directly to the reader. She and Tobias, the working class man, are the two voices who comment on the actions of the great men of power around them. That was intentional.

On how authors can help stop gender-based violence:

How can writers contribute to the collective effort? Write the truth about gendered violence loud and clear, and hope that even one person reads it. Fantasy is the pre-eminant genre for writing about power and violence. So write about power and violence and make people think about it. I read a brilliant academic piece of ASoIaF, pointing out that A Storm of Swords and A Feast For Crows capture the reality of the peasant experience of war better than most histories of the Wars of the Roses, different armies trampling across their lands killing and raping and stealing, ‘hail the true king, down with the bad guys!’ then next week it’s the other lot saying and doing exactly the same thing … That’s what fantasy can do. Has an obligation to do. Go read u/MichaelRFletcher ‘s BEYOND REDEMPTION, and see what a fantasy novel can say about politics and violence.

…

NEVER write a lengthy explicitly described rape scene.

NEVER use sexual violence as the sole motivating factor/backstory a female character has.

NEVER do what they did in the TV series Rome and have a woman be the victim of male violence and then happily marry him.

Showing the reality of gendered violence is profoundly important. If I had been more aware of how commonplace and unassuming and unspectacular gendered violence can be, maybe I would have realised sooner what a particular person was doing to me. But that’s very different from using gendered violence to titillate the reader. Or as a lazy way of defining a whole character. I’m sure I can be accused of rank hypocrisy here, as I write very lengthy, erotised accounts of male-on-male battle violence. But as a woman who has herself been the victim of gendered violence, these things seem necessary to say.

On what she’s working on next:

A noblebright fantasy about a poor common farmboy who discovers he’s actually a prince and has a near-divine right to save the girl and rule the world, and everything will be fine and good and sunshiny once he’s been crowned by the kind, wise and deeply spritual chief priest . Obvs.

Or maybe not.

Seriously, and brilliantly building on both question above, I’ve started a new thing exploring the life of a woman with young children in a war situation. Her character emerged in my head very clearly and I’m exploring her life. But it’s at a very early stage and I can’t say much more about it.

And, of course, there’s the grimmer than grimmer than grim series I’m co-authoring a serial for Grimdark Magazine with a certain God of Grimdark Mr Michael R Fletcher author of the absolutely brilliant MANIFEST DELUSIONS series, whom you may have heard of. It’s a lot of depraved fun, although we’re rather driving our editor up the wall with our total lack of organisation and general ‘why let a little thing like plot get in the way of a good dirty joke?’ attitude.

On the House of Grimdark:

I have personally apologised to Joe [“Lord of Grimdark” Abercrombie] for the whole ‘am I his mum or are we married?’ thing. And we were on a panel together last week with Rebecca Kuang, the three of us all solumnly announced ourselves as ‘Lord Grimdark’, ‘Queen of Grimdark’ and ‘Grimdark’s Darkest Daughter’ respectively. There’s a Sir Grimdark, a Grimmedian …. a whole House of us. Our sigal is a flayed-alive bunny rabbit and our words are ‘Do you have any idea how embarrising it is formally complaining that your Ocado order is half an hour late from this twiter account?’

Check out the rest of Anna Smith Spark’s AMA for more, including book recs, craft discussions, fun facts (did you know she has a pair of “heelless high-heeled Mary Janes covered in metal spikes” she pretends are the “broken blades of Marith’s enemies,” dubbed the “Shoes of Broken Knives”? You do now), and more. And for an even deeper dive into the grimdark genre, check out her piece “Grimdark and Nihilism” at Grimdark Magazine.